James Joyce’s Ulysses has a reputation for being a monumental and, at times, intimidating work. Yet, hidden within its dense pages are moments of profound simplicity. One of these can be found in the opening of Episode 4, “Calypso”, where we are introduced not only to the protagonist, Leopold Bloom, but also to a talkative cat. For those who have always hesitated to tackle Ulysses, this scene offers a small but representative taste of Joyce’s genius, as well as his subtle understanding of the feline universe.

A Change of Scene: The World of Leopold Bloom

The first three episodes of Ulysses follow the young teacher Stephen Dedalus. These pages are dense and cerebral, suspended on unsteady ground. In “Proteus”, we follow Stephen on a walk along Sandymount beach, lost in his thoughts. He stops to observe a dog carcass, only to be abruptly brought back to reality by a live dog that runs toward him, barking nervously and erratically, an echo of his own anxious inner life.

In Episode 4, “Calypso”, the tone shifts dramatically. We meet Leopold Bloom, a middle-aged advertising agent and the true heart of the novel. The setting is his home at 7 Eccles Street. The atmosphere softens: a frying kidney on the stove, a letter from his daughter on the table, and a cat weaving between his legs. The narrative’s rhythm becomes slower and more peaceful. Bloom feeds the cat before taking breakfast to his wife Molly in bed, whose impending extramarital affair hangs over the day.

Empathy and Purrs

Bloom cannot help but notice the animal’s independence. He admires her intelligence and even imagines her point of view, thinking of her in personal terms, as a “she” rather than an “it”:

They call them stupid. They understand what we say better than we understand them. She understands anything she wants to. Vindictive too. Cruel. Her nature… […] Wonder what I look like to her. Height of a tower? No, she can jump me.

This is not merely a humorous observation, it reveals Leopold Bloom’s keen empathy.

Joyce does not simply register the cat’s presence. For a few lines, he seems to slip into its mind, experimenting with a feline stream of consciousness: “Prr. Scratch my head. Prr.” He also uses onomatopoeia like “Mkgnao!”, “Mrkgnao!”, “Mrkrgnao!”, “Gurrhr!” to let us perceive the different nuances of a cat’s language.

In her essay “Tatters, Bloom’s Cat, and Other Animals in Ulysses”, Margot Norris points out how the cat in “Calypso” offers a rare glimpse into a non-human inner life. It’s a moment that is simultaneously funny, tender, and instantly recognizable to anyone who has ever shared a kitchen with a cat.

Love without Possession

Bloom’s life is both mundane and complex, only seemingly ordinary. A large part of Ulysses revolves around his wandering through Dublin while the shadow of his wife Molly’s affair remains in the background. Bloom’s character is the key to their relationship, as Molly herself affirms in her final monologue: “[…] yes that was why I liked him because I saw he understood or felt what a woman is and I knew I could always get around him and I gave him all the pleasure I could […]”. Indeed, Bloom is the “new womanly man”: empathetic, gentle, and not bound by the traditional male ideals of his time. From this perspective, the cat in “Calypso” is much more than a detail. Bloom’s patient and amused gaze at the cat’s independence suggests a broader capacity: to love without forcing, accepting the freedom of the other.

Cats in Joyce’s Life and Works

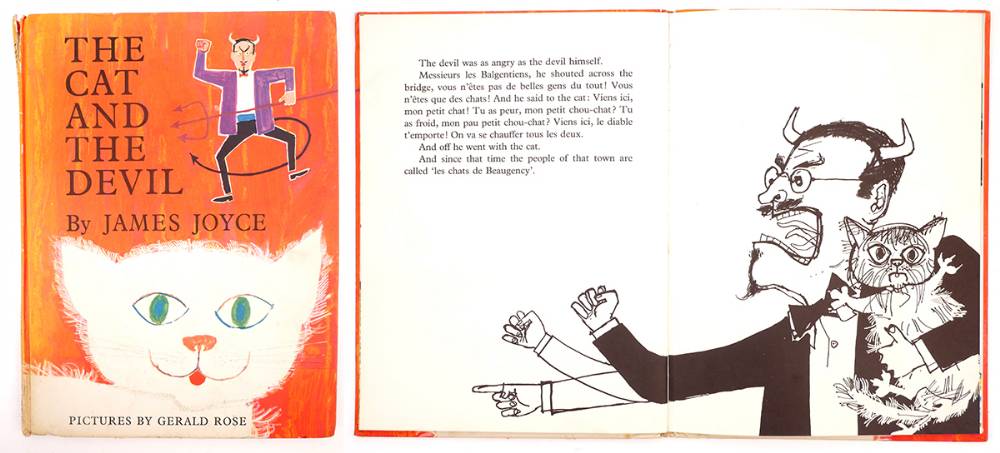

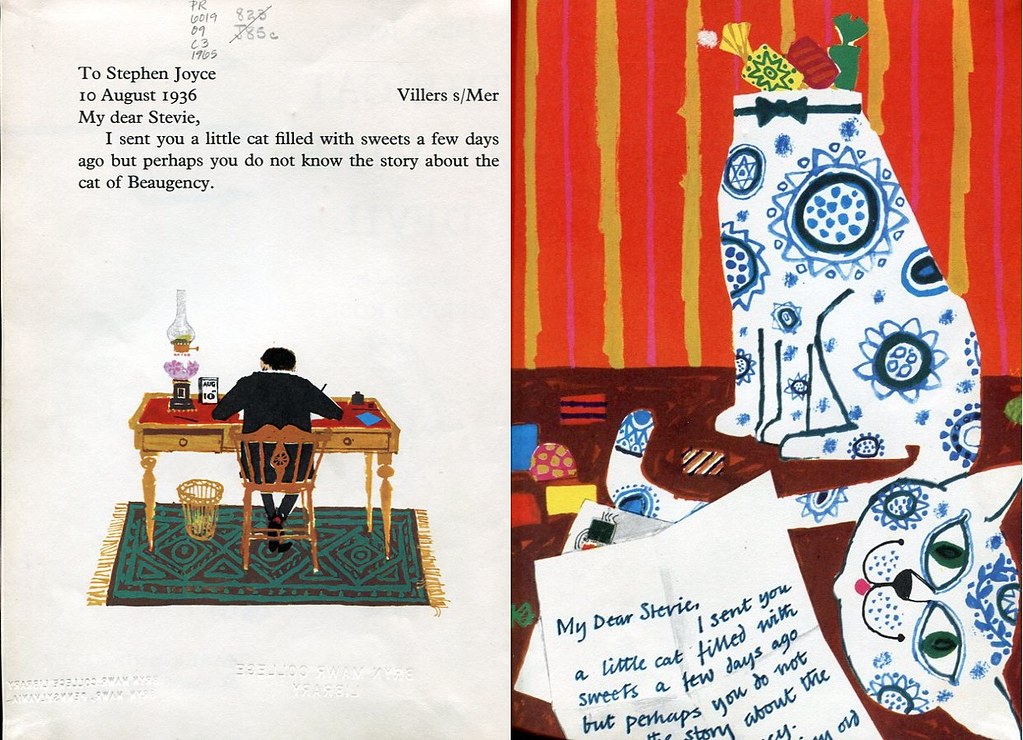

There is no evidence that Joyce ever owned cats, but he certainly held a certain fondness for them, as the cat in “Calypso” is not the only feline presence in his writings. In 1936, he wrote two cat-themed fables for his grandson Stephen, The Cat and the Devil and The Cats of Copenhagen, both published posthumously. In the latter, Joyce jokes that in Copenhagen “there are no cats – just too many policemen,” weaving a whimsical tale of feline freedom and cheeky urban anarchy. As Sadie Stein notes in her Paris Review article “Cat Fancier” (2014), these “bizarre and lyrical” fables show Joyce using cats as vehicles for satire and a gentle mockery of authority. But these stories also show the same amused affection for felines that we sense in “Calypso”, suggesting that the cat was a beloved figure in the Joyce family’s imagination.

In Finnegans Wake, we also encounter Issy, the nymph-like daughter of HCE and ALP – a character in many ways echoing Joyce’s troubled daughter, Lucia Joyce, whose extraordinary talent and fragility marked a life shadowed by mental suffering and institutionalisation. Issy embodies an unsettling blend of precocious sexuality and infantilism, rendered emblematically by her close ties to the feline world: in the text, she is sometimes represented as a domestic cat, known as “Buttercup” (FW 561.12) or “Biddles” (FW 561.36). In these images, a complex metaphorical interplay between feline qualities, female youth, and sensuality returns. But to truly delve into this theme would take us into Joyce’s nocturnal labyrinth… And venturing into this labyrinth would lead us well beyond the confines of this article.

Mkgnao! An Invitation to Discover Joyce

For those approaching Joyce for the first time, however, the beginning of “Calypso” is certainly an ideal starting point, much more so than the obscure pages of Finnegans Wake. In Bloom’s kitchen, the onomatopoeia “Mkgnao!” and the protagonist’s small gestures – feeding the cat, understanding its moods, wondering how he appears in its eyes – reveal a delicate attention, an empathy and a non-possessive love that transcend the domestic moment. In just a few lines, Joyce offers us a tender and ironic portrait of a cat, and through it, a portrait of a man. In these pages, there is already everything that makes Joyce so great. If Ulysses has always seemed inaccessible to you, try meeting Joyce in Leopold Bloom’s kitchen with his cat. You might find yourselves purring too.

Bibliography

- Joyce, James. Ulysses (1922), Episode 4 “Calypso”.

- Joyce, James. Finnegans Wake (1939).

- Joyce, James. The Cats of Copenhagen (1936, published posthumously 2012).

- Joyce, James. The Cat and the Devil (1936, published posthumously 1965).

- Norris, Margot. “Tatters, Bloom’s Cat, and Other Animals in Ulysses”, Humanities 6, no. 3 (2017): Article 50.

- Stein, Sadie. “Cat Fancier,” The Paris Review blog, March 17, 2014.

1 Comment

Anonymous · December 9, 2025 at 11:56 am

So interesting!